Getting Dressed While The World Burns

Kim, there's people that are dying!

There’s nothing quite so freeing as wearing an outfit you feel really, really good in. It’s almost as satisfying as a good hair day, which is of course, akin to what being God must feel like.

Despite this, I find myself an at-risk case for apathy creep. When getting dressed in the morning, I wonder, ‘Why bother? The world’s on fire anyway.’ It’s the perfectionist’s balance between truly not giving a fuck and pretending you don’t give a fuck. It’s voyeuristic, it’s obscene, the way I think about myself too much.

However, thinking about things too much is just what I’m good at and if there’s one thing I like to do, it’s beat a dead horse. Think of this essay as a sister to October’s first essay, “Gingerbread and the Epistemology of Good Taste”. That essay covered how algorithms flattens taste over time, this essay will make the case for preserving taste internally for the sake of community morale.

Style is how we practice attention, how we tether ourselves to the world through color, texture, and form. Through this lens instead, we find that getting dressed when the world is on fire is defiance of the systems that suck the joy, pleasure, and hope out of us. Building a life of authentic taste as a means of resisting that looming apathy creep.

At its worst, fashion is escapism. At its best, endurance.

I Think You Guys Might Be Thinking About Yourselves Too Much

In our search for identity, it’s the act of living that moves us forward. Mental fatigue is inevitable, but even the smallest act of purpose builds momentum.

Every bit of effort is a brick in the wall that keeps despair at bay. And boy, do we see a lot of despair these days.

Work, in any form, gives life meaning. It sharpens our emotional and creative depth so we can face our private, often invisible struggles. And I’m not talking about the work you do at your 9-5 necessarily, but the work we dismiss as “vain”, the daily rituals, which are the very foundation that steadies us. Fashion isn’t just personal; it’s how we show up in the world. You can’t create change by thinking yourself into paralysis. You do it by doing, by participating, even softly.

bell hooks reminds us in Art on My Mind, our uses of time and the choices we make are acts of “visual politics”: caring about beauty and presentation isn’t frivolous but how we position ourselves within culture.

Seen this way, our so-called “vanity hobbies” become tools of resilience. Choosing what to wear, curating taste, or simply showing up with intention can be quiet acts of rebellion. They free us from perfectionism and make goodness — rather, beauty — attainable again. The art of getting dressed, like the art of living, isn’t about achieving permanence. It’s about finding joy in what can’t be taken with you.

As Barthes wrote, fashion is a language. Choosing not to ‘speak’ it and to appear neutral or above caring is still a kind of speech. Even apathy communicates something.

All aesthetic choices, even ones labeled anti-fashion, communicate something to others. There simply isn’t a way to remove yourself from the narrative. Fashion, not just the concept of clothing, is an art form and language in one. And that’s always been true because across history, resilient people have used style as protest, protection, and prayer.

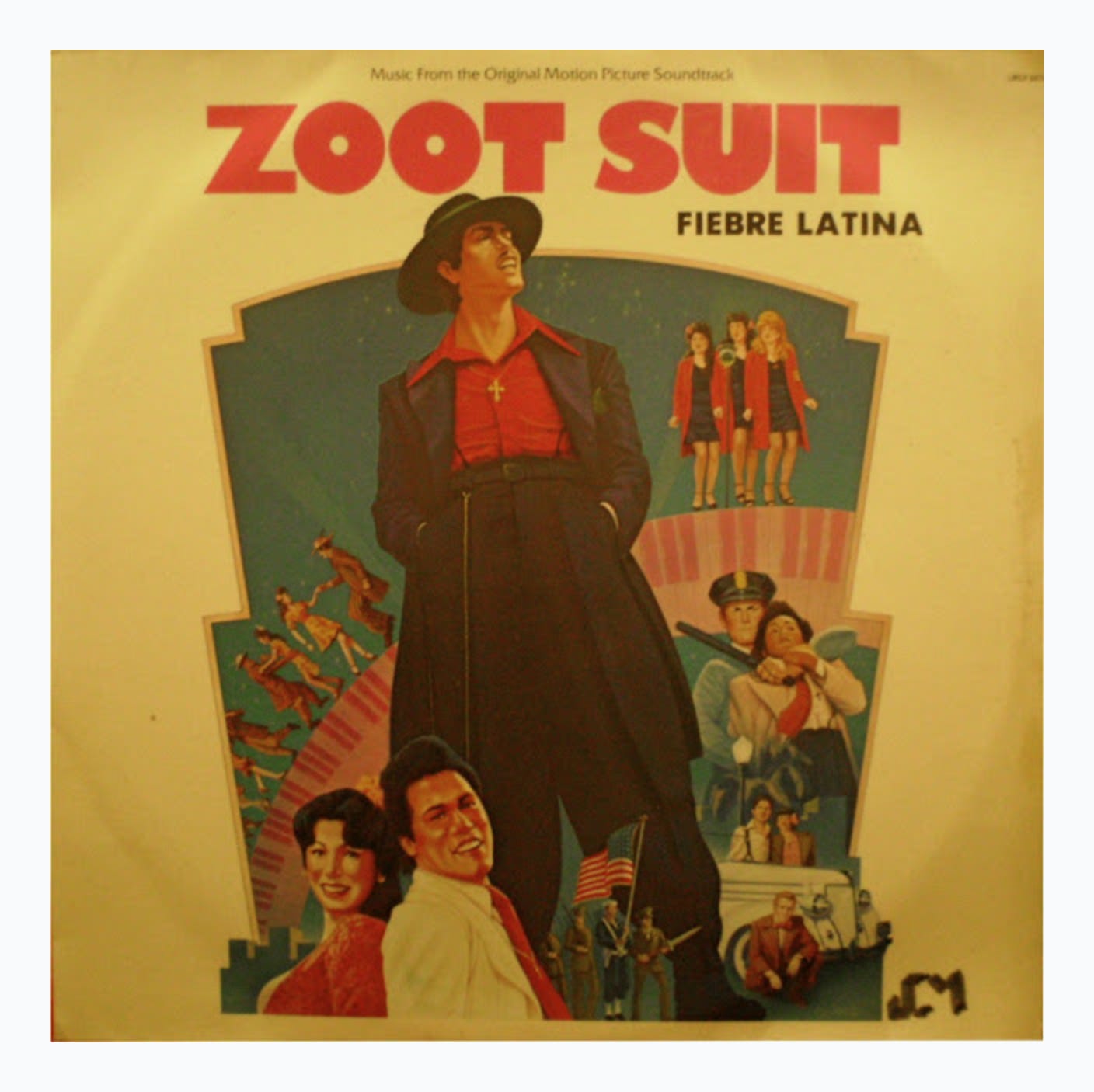

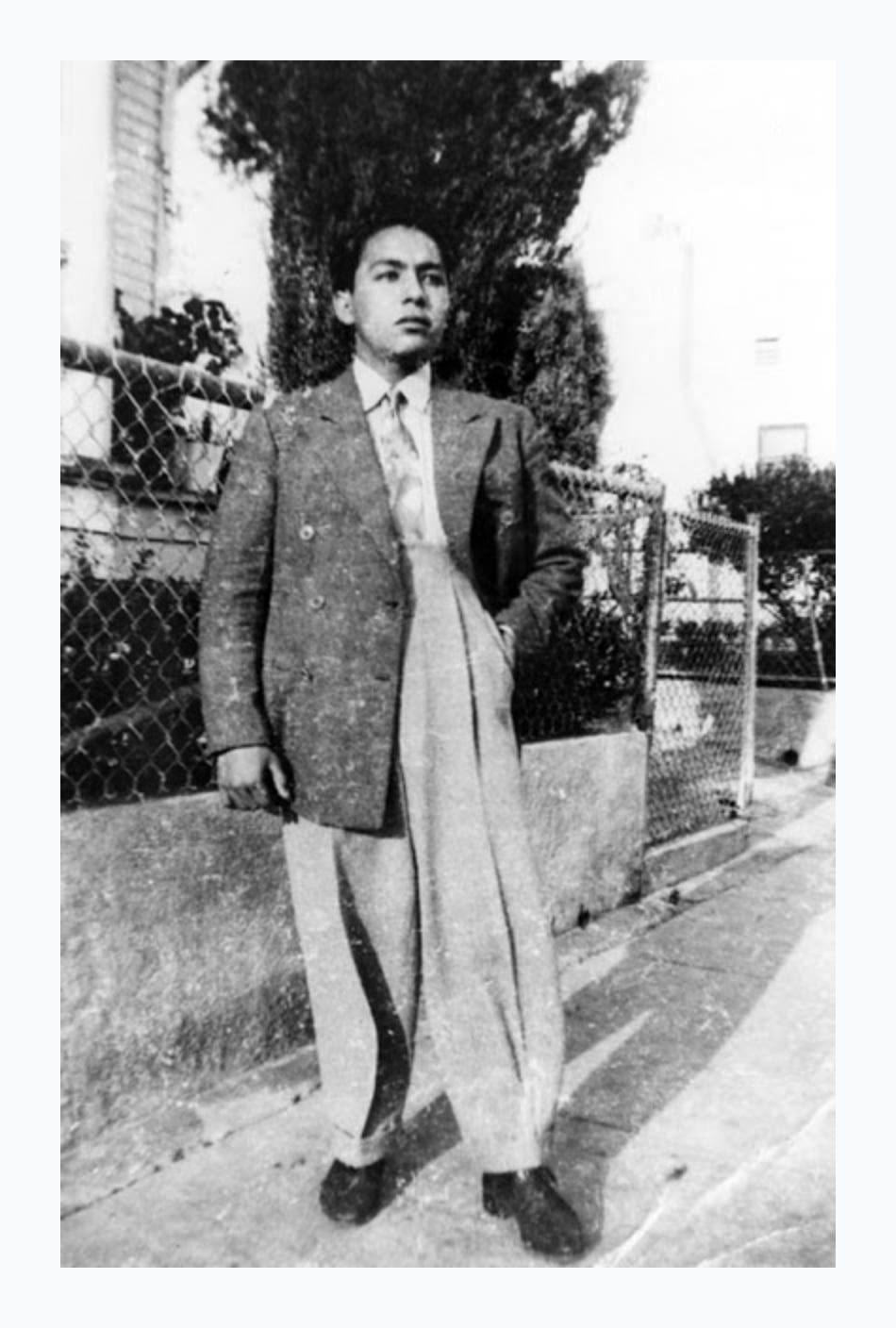

The Zoot Suit Riots

In the summer of 1943, young Mexican-American and Black men in Los Angeles wore zoot suits: oversized jackets and trousers that sprung from Black jazz cultures. They found themselves attacked by U.S. servicemen who saw the look as provocative.

Because we rationed much of our resources to ensure war time materials, when something like wool was rationed for the war, it was reserved only for what was deemed necessary, such as military blankets and other gear. Civilian clothing did not make the priority list, so a garment like the “Zoot Suit”, which was popular in Latino youth cultures like pachucos, would have been viewed as allegedly “unpatriotic”.

The riots that followed were triggered by the clothing itself but were more about how these men chose to be visible in a society hell-bent on erasure.

“Local papers framed the racial attacks as a vigilante response to an immigrant crime wave, and police generally restricted their arrests to the Latinos who fought back. The riots didn’t die down until June 8, when U.S. military personnel were finally barred from leaving their barracks.” (Zoot Suit Riots, history.com)

Wearing a zoot suit then was a charged act of participation, potentially making you a target to those who were, to put it frankly, racist. That moment illuminates the heart of this essay: it’s precisely when life is heavy that choosing to dress with intention is how you tether yourself to your presence, your story, and your society. This story is particularly relevant today so I really encourage you to do a deeper dive.

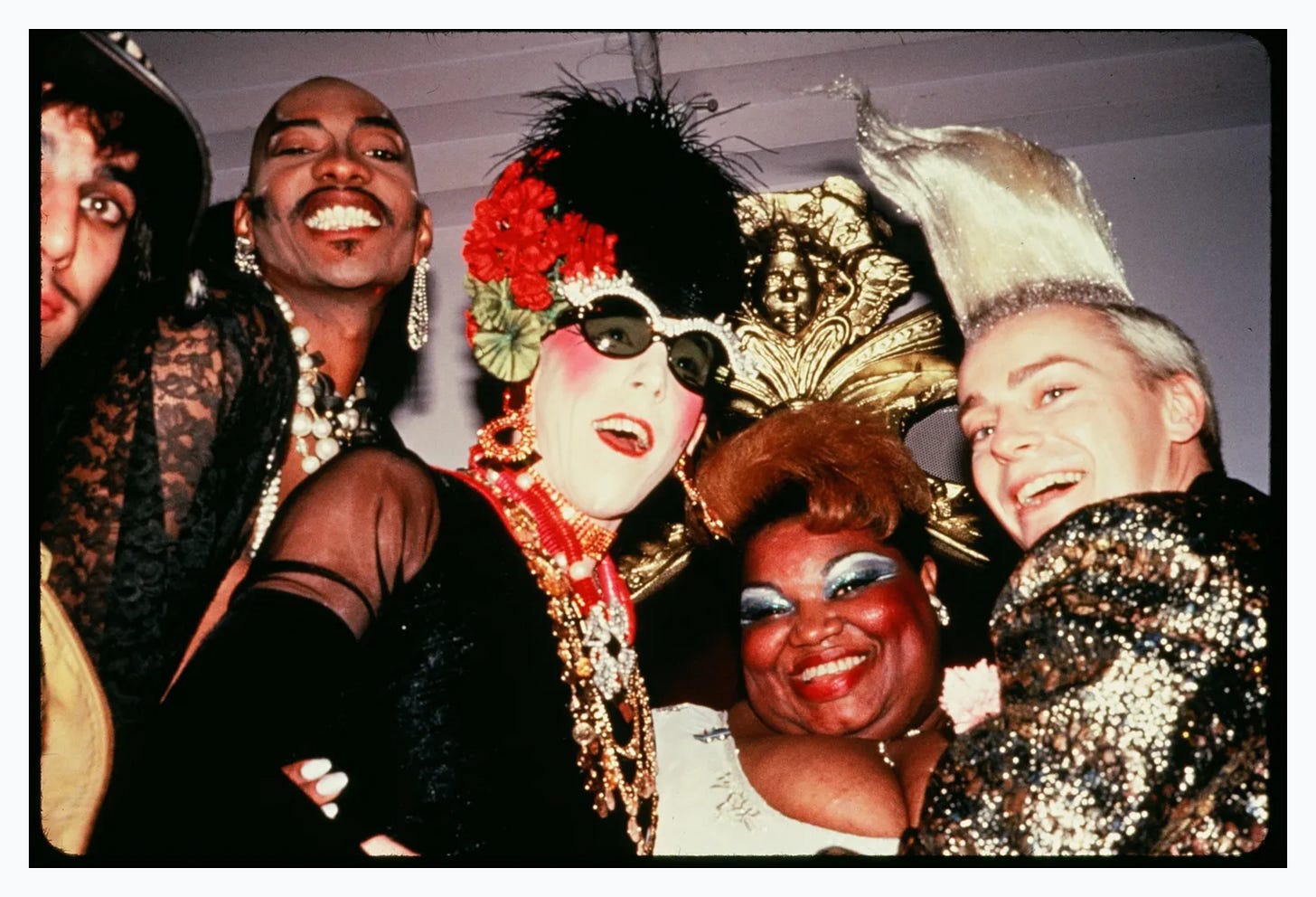

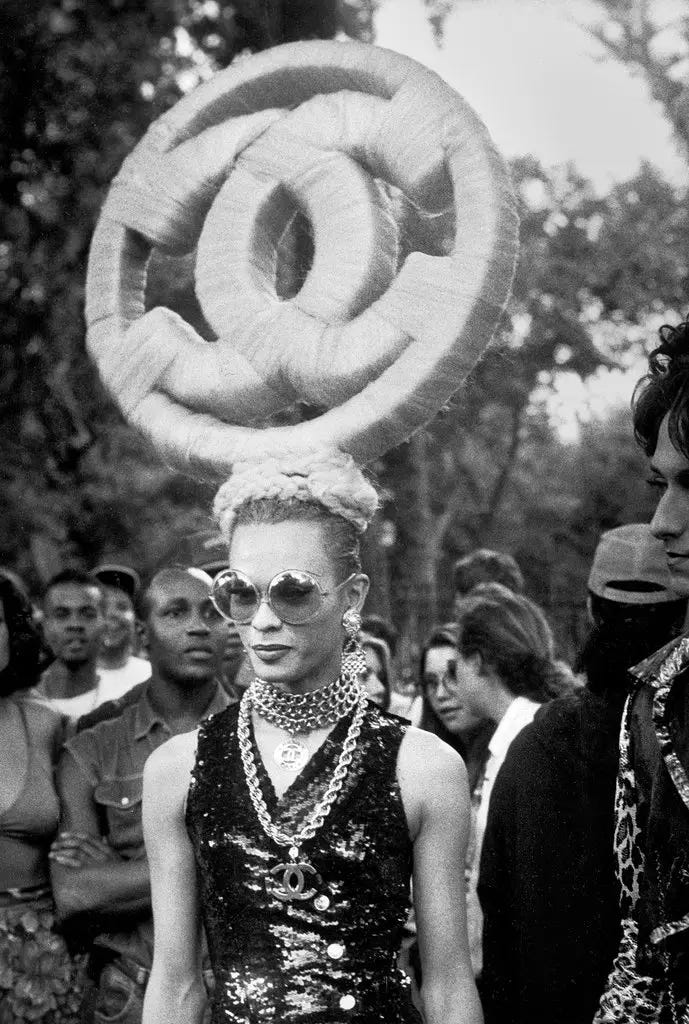

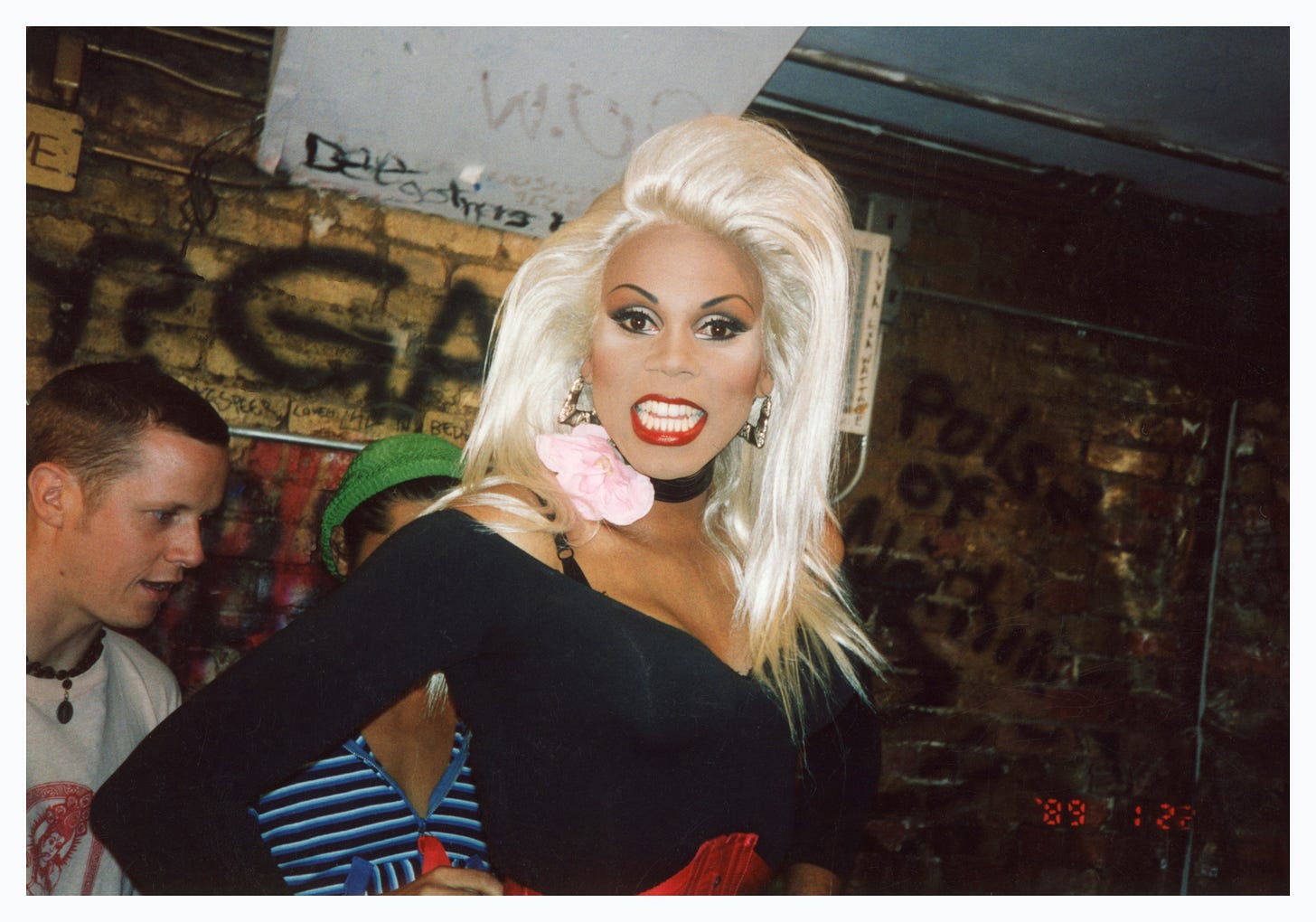

The Lessons Are Calling From Inside The Club

In 1984, a group of (sloshed) drag queens stumbled from The Pyramid Club and onto the idea for Woodstock…but for drag. Thus, Wigstock was born. It was in the 1980s specifically that drag culture became one of the most visible forms of aesthetic resistance. Amid the AIDS crisis and political conservatism, queer communities used fashion as both armor and art. Sequins, wigs, and exaggerated femininity were not just performance, but a declaration of life in the face of systemic neglect and public hostility.

While mainstream society viewed drag as deviant, inside ballroom houses like those chronicled in Paris Is Burning, fashion became a language of chosen identity and survival.

To “walk” in drag was to say, I am here and I am beautiful even if the world refuses to see me that way. Like the zoot suiters before them, these performers turned clothing into protest by using style to carve out visibility in a world that sought to erase them. Dressing up was not escapism; it was an act of endurance, a way to stay tethered to joy and selfhood when everything else demanded invisibility.

In the words of Dorian Corey from Paris Is Burning: “In a ballroom you can be anything you want… you’re showing the straight world that I can be an executive.”

Watching New York Before Watching New York

Bill Cunningham has a quote that I particularly love,

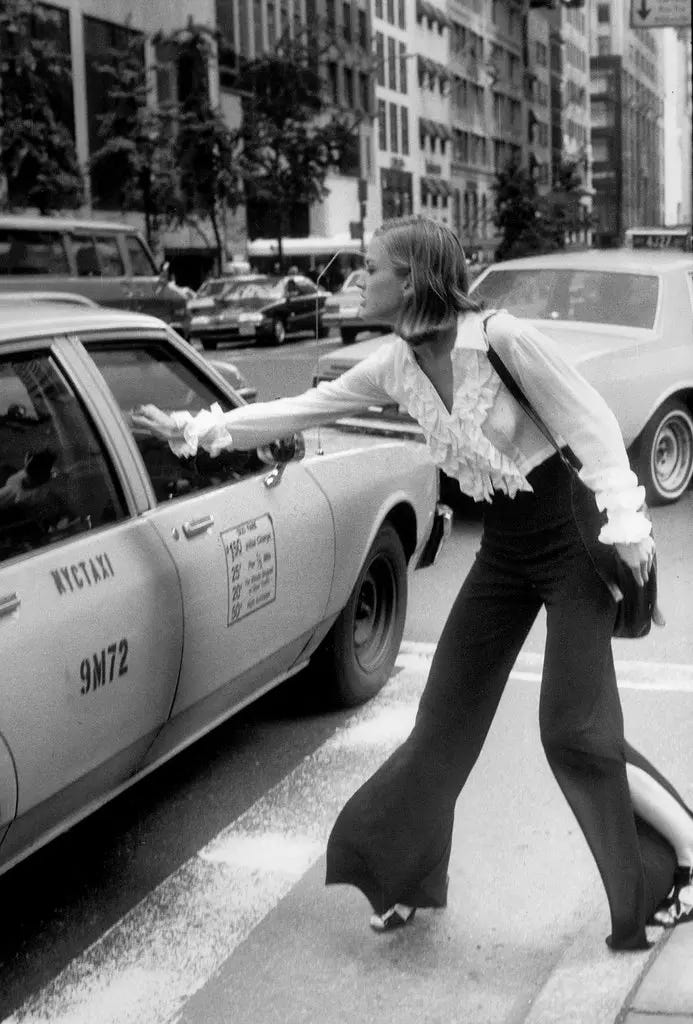

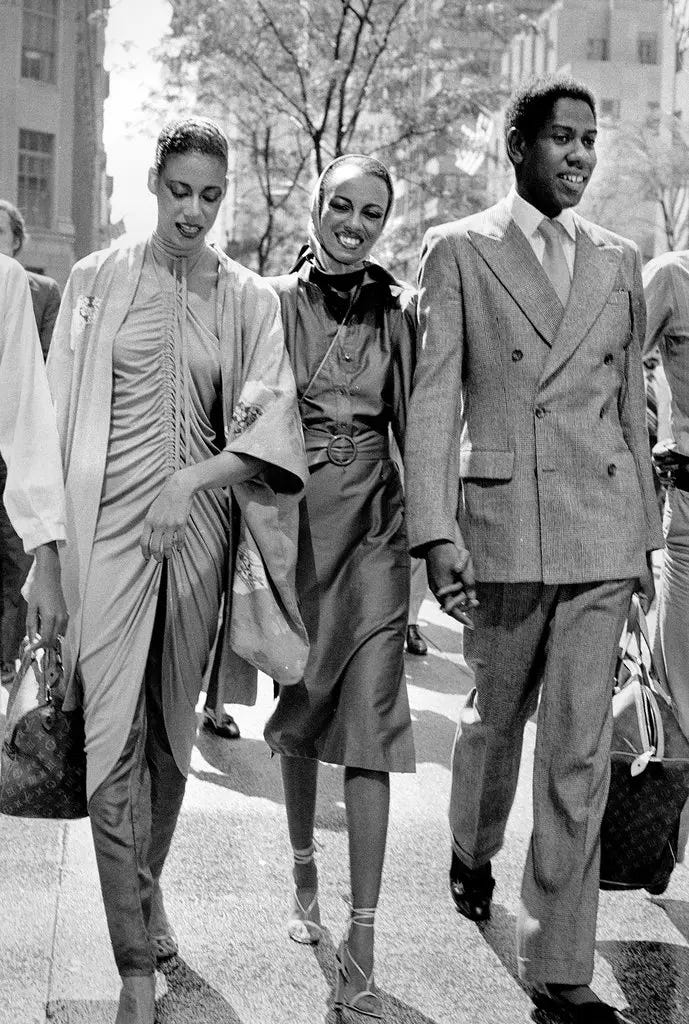

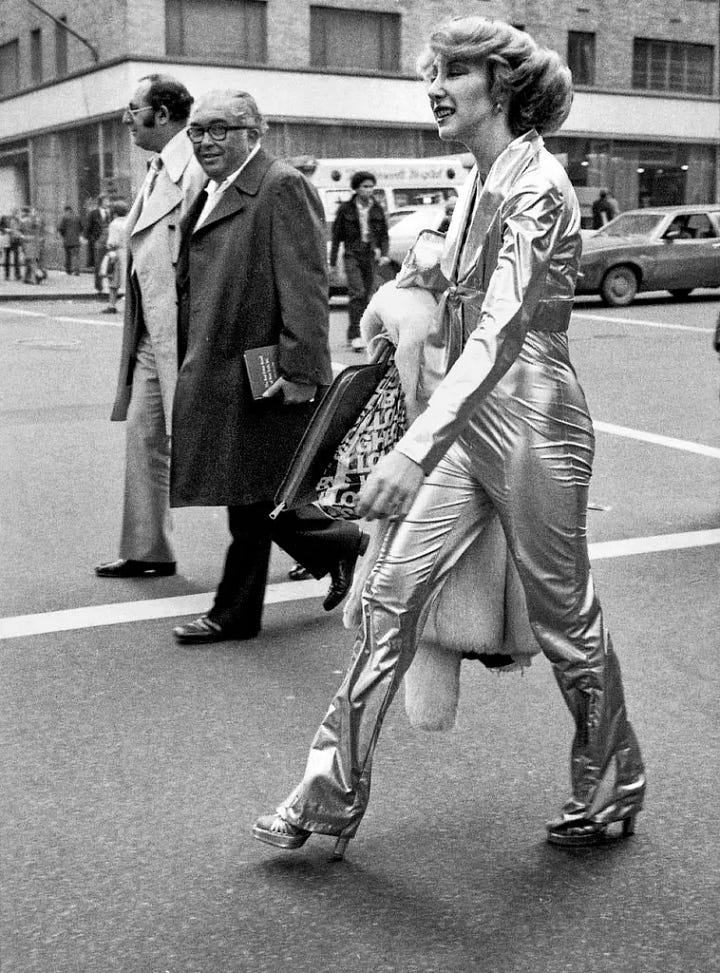

“Fashion is the armor to survive the reality of everyday life.”

You could view that as bleak perhaps, but it’s the difference between meeting an obstacle with insecurity vs authority. It’s a way to take back a sense of autonomy, of power.

Cunningham rode his battered bicycle through New York City in the 80s, photographing ordinary people whose style refused to be passive.

Thank you for making it to the end of this essay and hopefully, through the first entire month of the Gatekept series. I’d like to encourage you to finish this week’s syllabus and join our chat to suggest new topics for November. Beating a dead horse is also obviously encouraged, so pop by even if you have nothing new to say or just some shit to talk. And tomorrow, when you’re peering into your closet, when you’re staring down the barrel of apathy creep, choose to build your endurance by getting dressed.

I l joined sub stack because I saw someone talk about "gatekept". I really enjoyed reading this. It was well written and knowledgable in a fun way.

I found your substack through an Instagram creator’s review and looked you up. As someone who isn’t from fashion but loves to educate herself on fashion, I’m super happy to be on your platform! :)